I Hate Matlab: How an IDE, a Language, and a Mentality Harm

This blog post is inspired by a few Matlab-related tweets of mine, which turned into days-long discussions with fellow science and non-science tweeps. Those tweets of mine in turn are motivated by two main things: my desire for programming in psychology, neuroscience, and science in general to be taught and taught well, and my desire for students to learn transferable skills more generally. This blog post is premised on a number of themes which came up on Twitter. The great need for scientists to be able to code. The fact that Matlab is akin to bad training wheels on a bicycle, which never aid with learning to ride, but are used over again because they are better than walking. And the idea that while there is a best tool for every job, not every tool is best for any job. The discussion on Twitter was motivating and so I promised everybody I would write up what I think. So this blog post is about how I think teaching Matlab, the whole ecosystem not just the language, within psychology harms students more than it helps them in many cases in my experience.

To clarify, Matlab used to be the best tool for many things. Before things like the NumPy/Matplotlib/Jupyter trilogy, it was probably the only tool that had “everything”. When Matlab first came out, the alternative was Fortran (which has goto statements, if you don’t know why this is scary, never mind, you’re lucky). But I believe it is now more a cause of brain-rot than mind-expanding awesomeness (please do not watch Arrival just to get this Sapir-Whorf reference). It is now more user- and science-jail than a freeing experience that allows us to make prototypes fast (it of course still does the latter).

If you are a proficient coder and love Matlab, then this blog post is not really for you. Importantly, my intended audience are those who wish to see an improvement in the teaching of programming within psychology. I am talking from the perspective of my experiences within my field: psychology and cognitive science. I have designed from scratch: a course, that I taught when I was working as a postdoc at Oxford; and a workshop, while I was a PhD student; both with the aim of teaching the principles of coding before diving into Python specifically for psychology students. I also want people in science to have dependable transferrable skills, to be able to move to other languages, as well as having as much fun as possible while learning. Because of my training, I am privileged enough to be able to pick up a new language in a couple of hours. I want others to have such skill-related opportunities too, not only because it is useful for science as an endeavour to have skilled researchers, but for us as individuals: if one emerges from their degree a coder one will have more opportunities (both within and outside science).

To reiterate my titular claim: the way we teach Matlab in psychology appears to be more harmful than helpful. I would like us to move beyond Matlab because the ecosystem it provides is a dangerous attractor, which many of my peers and my students involuntarily get sucked into. In this post I will outline the main reasons why the Matlab ecosystem and language are as provocatively described above. I intend to use “Matlab” to mean the whole ecosystem: the IDE, the language, and the mentality it brings about because I think they are inseparable. In the same way “C programmers [allocate] their own damn memory, probably right after building their own computer out of rocks and twigs”, Matlab coders within psychology also have and create a culture around them aided by the IDE and the pre-existing community they have joined.

Limited Skill Transfer

Firstly, Matlab is not sufficient to provide us with a transferable programming skillset. Matlab provides a programming environment in which nothing, at least superficially, seems hard — and thus nothing meaningful about coding itself is learned. We do not need to worry about namespaces, nor even functions too much. And we do not need to learn anything too complex to get some OK-looking figures. This is great for prototyping — we can produce something that works well enough impressively quickly. But this comes at a huge cost to us as a newbie coder. We have not learned any of the important skills that would enable us to pick up another language. And we will undeniably need to pick up other languages because that is the state psychology is in — e.g., R is becoming the standard for statistical analyses. Yet we just learned a language that does not help us do that since it did not push us to learn the basics of what other languages have at their core.

To put this another way, when one is learning to drive they do not tend to learn to drive using an automatic gearbox. They learn to drive with a manual gearbox and it is tough. Learning the harder of the two types, manual, allows us to then easily transfer to the easier of the two if need be. In the case of USAmericans, they mostly learn to drive an automatic gearbox and almost never learn manual (because their skills do not transfer easily). Although the metaphor is simplistic, it suffices to explain why Matlab is not the best language to learn, it is a car with an automatic gearbox. We cannot easily transfer what we have learned to driving stick and in fact licences for just automatic transmission exist in my home country and the UK: if you learn just automatic you cannot be expected to know stick, whereas if you learn manual transmission you know “everything”.

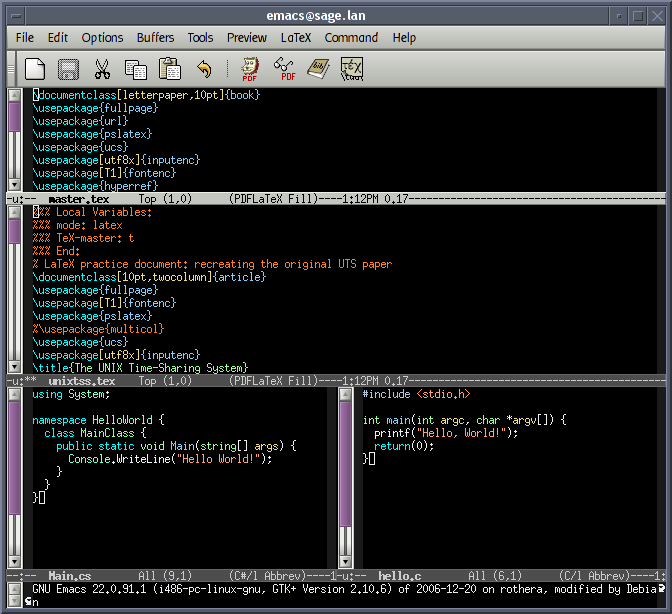

Furthermore, I posit that Matlab knowledge can make it harder than absolutely no programming knowledge for us to shift to another language. Matlab has an IDE that provides GUI functionality that allows us to edit variables dynamically like in Excel, which we know causes demonstrable problems. It causes some of our students to think that the Matlab IDE is what programming is, in much the same way some of our students think SPSS is what statistics is. Furthermore, high dependence on manually editing things is extremely bad because our workflow will not be reproducible nor replicable.

In addition, all the bells and whistles of the IDE and the GUI never force us to think about variables deeply (since we can always visualise them). This exercise in keeping a mental model of what the code is doing, writing down what the code should be doing, imagining the data structures, etc., is a skill one needs to be developing. More than once I have been asked to help people who were editing their variables in the GUI and hence did not properly understand their own code nor how to debug it. This is not their fault, but had they learned to code without this they would never have picked up such terrible habits. They had not learned exactly what a loop was and a lot of other helper scripts worked just fine, so they had no feedback that editing in the GUI is maladaptive per se.

In most other languages: there is no GUI and there is no IDE that has the language baked in. This results in many of us using Matlab by just pressing buttons and hoping something useful will come out the other end. And this observation, shocking though it may seem, that this is what we and our students do, has been backed up by so many of you over chat and Twitter. The GUI and IDE crutches will be snatched away from us as we will have to learn to code all over again — something we need never have to do if we had learned using a manual gearbox/not Matlab.

Matlab puts a ceiling on what kinds of projects we can do both in size and in scope. Optimising for hardware, needing to lower space and time complexity, wanting something very specific like web-scraping, etc., are all tougher within Matlab. This is because Matlab is more a domain-specific than a domain-general language, it is centrally controlled, and the GUI and IDE cannot cope with large projects easily (although there is a command line mode, which we will be predominantly uncomfortable with given we only know Matlab).

To further underline my point, Matlab explicitly teaches us some very unorthodox programming principles. Some “features” do not exist in (m)any other languages, and certainly not in any we will likely want to learn in the near future (Python, C/C++, R, Julia — even LaTeX). For example, we are not allowed to have more than a single externally accessible function per file, and that file must have the same filename as the function we wish to access. In essence this means we cannot have more than a function per file if we are, e.g., trying to code up a library in a clear way. Matlab does not permit us to store all our global variables in one file, e.g., if we need constant values. Due to all this, Matlab promotes spaghetti code. This adds to why many of us feel embarrassed to share our code online. We never learned to write neat code because Matlab allows us to be quick and dirty without any repercussions.

Perhaps most flagrantly, arrays in Matlab start at 1. One has no idea how maladaptive this is until they move outside Matlab. Computer science starts from zero for a reason. If we want to learn generalisable skills, learning that indexing starts at 1 will hinder us, perhaps even cause us to introduce very nasty hard-to-find bugs when we move outside the Matlab ecosystem. All these put together cause us to get more confused by new languages as the baggage we carry with us from learning Matlab needs to be actively unlearned and inhibited.

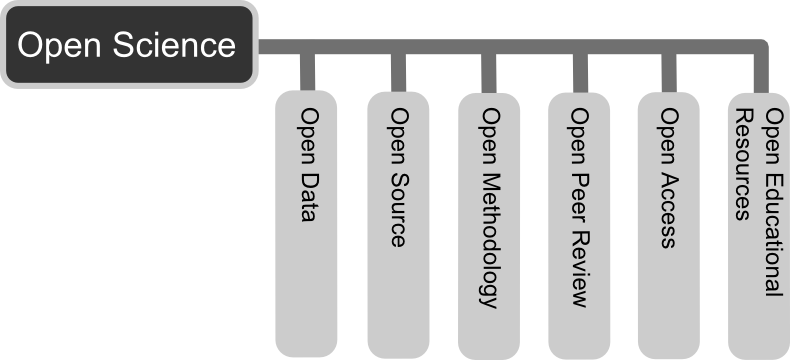

Closed Source Means Closed Science

Secondly, Matlab is closed source, proprietary, and prohibitively expensive if you have to buy it yourself. They obfuscate their source code in many cases, meaning bugs are much harder to spot and impossible to edit ourselves without risking court action. Moreover, using Matlab for science results in paywalling our code. We are by definition making our computational science closed.

Many people in the mutually inclusive open science and open software movements hope to see Matlab surpassed sooner rather than later and some even think it is inevitable. By extension, people in these movements tend to think freely deciding to use Matlab (and indeed any closed source software) in science is at least questionable and at most unethical. I believe in free and open software and science, so I am in principle opposed to Matlab’s grip on science. This does not mean I believe the science done with Matlab is in any way worse in and of itself. By the same token, scientists who believe in open access do not think that science published in closed access journals is “bad science” — they think it is not the best publishing practice. Sadly, one can either be for open science or against it. So unless Matlab’s “core values and conviction to “Do the Right Thing”” start to also include open source and science, Matlab is incompatible with our aims.

Something that pains me immensely, and indirectly affects all Matlab coders is the incompatibility between Matlab versions. The main reason for this is, unlike Python or C++ or pretty much all languages out there, there is no Backus-Naur form for Matlab to my knowledge. This means that Matlab has no official and formally-specified grammar, it could, but it does not. This is incredibly bad if true, and explains the compatibility problems, making Matlab more like Microsoft Word (which is not backwards compatible and not a programming language). It also means Mathworks does not have to stick to any rules for the grammar of Matlab, they can change it on the fly. And by the same token, Octave compatibility is hard to maintain because the language is not defined.

Importantly, over and above the fact it is not open source, I propose Matlab (and thus similar languages like Octave and SciLab which are open) should not be our go-to languages for the reasons outlined herein. To re-iterate, Matlab is not the best language to teach our students and peers for pedagogical, skill transfer, and practical reasons over and above the ethical/openness reasons. These reasons in and of themselves serve to discredit Matlab and demote it from its place as the primary programming language for teaching in psychology.

Conclusion

In a nutshell, Matlab creates an environment where we learn how to code without ever doing anything too difficult, without ever developing skills that really transfer, and without ever understanding the core of what coding is about. I want us to be better equipping ourselves and our students for both life in science and giving them useful skills for life outside science. The default position in my part of science is you teach Matlab and then that is it. I do not levy these criticisms against those whose of us who use and teach a multitude of languages (including Matlab). I am focussing on the majority of us who teach and use for all intents and purposes only Matlab.

GUIs and IDEs are great — just like once we already know how to drive using a manual transmission we can easily switch to automatic — but they predominantly do not push us to develop our skills further. If we want to we can switch to a fancy IDE after we already know the tougher stuff. We learn multiplication tables off by heart before we switch to using our smartphone as a calculator. I am assuming we all want to develop our technical skills appropriately, so inevitably we will need to carry out much more complex tasks, like writing a bash script or compiling something from source — all these things are skills we need to be building up slowly over time. Matlab allows us to live in a lovely world where everything is easy but from which we cannot escape. Research will throw harder programming tasks at us than quickly making graphs or fast matrix multiplication. Thus we need to accept that sometimes learning new things can be hard (as well as fun).

Some will push for their own favourite language, e.g., Python. Nonetheless, as long as we move away from the paradigms the Matlab ecosystem enforces, we will have made serious gains pedagogically. I hope I have convinced my intended audience that even though Matlab has been the go-to language things should be and are rightfully changing. For examples, even within engineering where Matlab has a historically strong hold its widespread use is being eroded — the engineering department at Cambridge decided to teach Python instead.

Programming education in psychology can be better. Other languages provide more replicable and reproducible workflows, more opportunity to learn transferrable skills, and communities centered around open source and open science. If we can teach the Matlab ecosystem, then we can make a small step for great gains and teach a better more open ecosystem. We must teach the core concepts of programming and we must teach them well. We are in the midst of transition from closed source to open source, closed science to open science, black box workflows to reproducible and replicable workflows. Let’s make this transition happen by equipping our students and ourselves with the most appropriate skills.

Thanks

This blog post would not have been possible without discussions with my Software Sustainability Institute co-fellows and the institute’s staff, nor without the many many tweets from you all.

Related Resources

- White Paper: MATLAB to Python, A Migration Guide

- Learn Python on Codecademy

- matlab rant 2 by Benjamin Vincent

- MATLAB is a terrible programming language by Nikolaus Rath

- Morlocks And Eloi At The Keyboard by Neal Stephenson

Cite

@misc{guest2017matlab,

author = "Olivia Guest",

title = "I Hate Matlab: How an IDE, a Language, and a Mentality Harm",

year = "2017",

howpublished = "Blog post",

url = "http://neuroplausible.com/matlab"

}