Path Model Q&A

-

Article:

- Guest, O., & Martin, A. E. (2020). How computational modeling can force theory building in psychological science. PsyArXiv. doi: 10.31234/osf.io/rybh9.

Anna Henschel and Stephanie Allan kindly invited us to discuss our (Olivia Guest & Andrea Martin) work How computational modeling can force theory building in psychological science at their reading group Glasgow ReproducibiliTea last week. So we decided to write up the questions we received in this blog post. It was a very enjoyable experience. And we’re very grateful not least because it’s explicitly aimed towards and for students and more junior people in our field — an audience we believe is especially able to learn how to improve their scientific reasoning and theoretical construction skills.

We went into some background on why we created our path model, why computational modelling is a useful tool to help refine our own thinking as well as the theories scientists propose. You can watch a video of us talking and answering a subset of the questions, kindly edited and uploaded by Anna. Below are some of the same questions (with very minor edits for typos and clarity and reordered for ease of answering) that we received while we were chatting — some of the questions we answered in the video might not be answered here and vice versa. Also some questions are not answered below because we are working on follow-up work that addresses them and so to save time and space here we’ll just skip those for now. Super importantly before reading this, read the manuscript as our answers are long and don’t really make sense without that context.

General Questions

I might be confusing things here: but what is the difference between computational modeling and careful operationalization (in the empirical circle)?

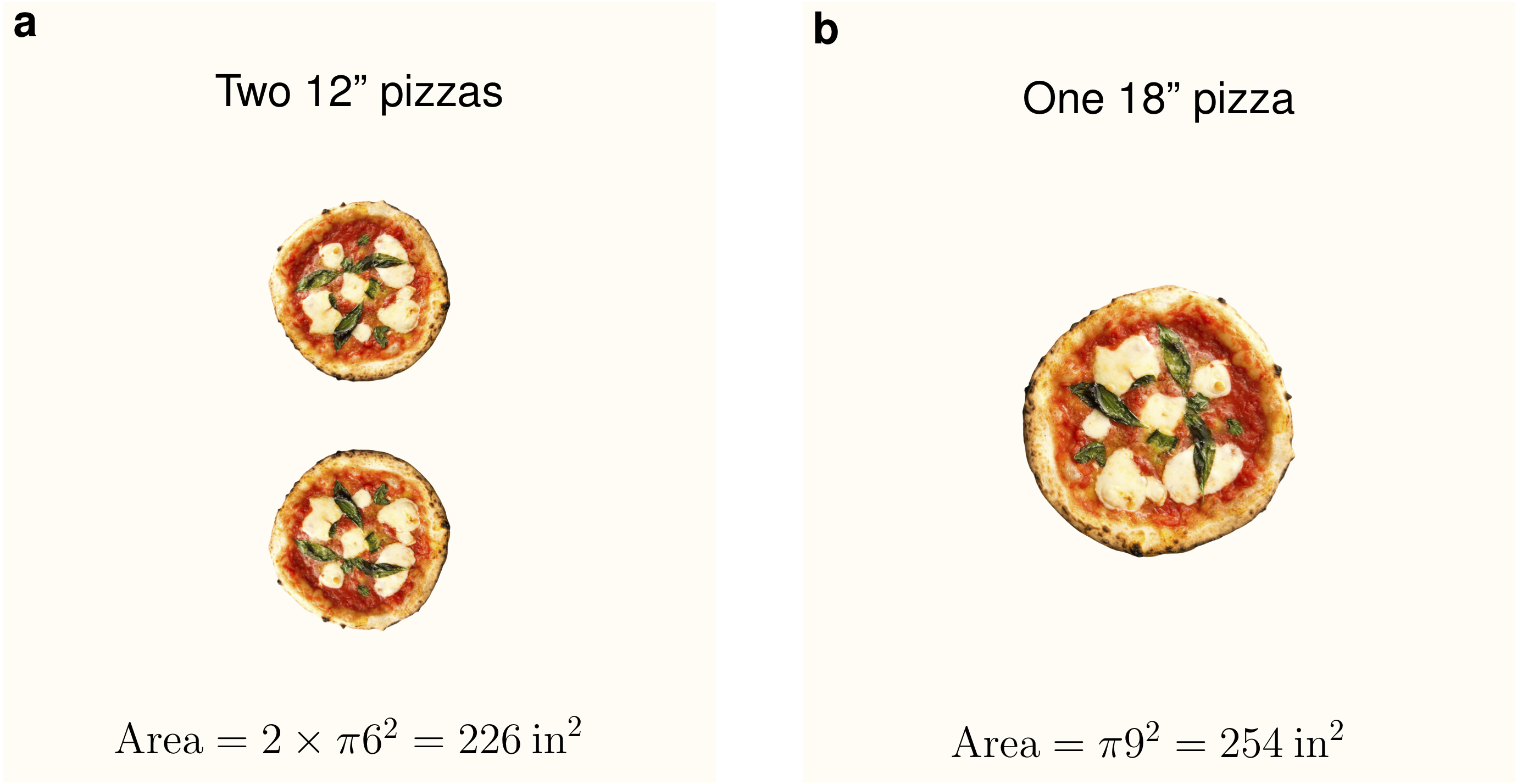

This is the difference in our path model between specification and implementation. Captured by this tweet, which served as the inspiration for the section The pizza problem:

Why we need computational modelling: even if everybody agrees what the area of a circle is defined as there are apparently people unwilling to execute the formal model itself and not only that but the results are counterintuitive. 😂https://t.co/c1SKgRAZMh

— Olivia Guest is on the job market! | Ολίβια Γκεστ (@o_guest) October 21, 2019

One question I had from reading the paper was you say that most undergrads in psychology leave knowing a bit about statistical models. From my own experience (aware other degrees might be different) I do not think there was as much focus on theory building. Do you have any ideas how undergrad education could incorporate theory building?

In our experiences of working at various universities, there is indeed not much explicit focus during undergraduate degrees on general theory building, setting aside computational or formal modelling of theories. However, what happens very often is throughout each module the historical and current accounts for psychological theories (and indeed frameworks) are very much expounded on. Students learn about, for example, how Pavlov explored dogs’ behaviours and created the ideas behind classical conditioning. These historical and contemporary stories of how scientists develop their understanding of a series of phenomena are how theories are built. What might be happening is that students are not ready yet (due to the deluge of information) to also zoom out and notice that theory creation and development is being signposted to them. This is a normal byproduct of learning new things. Some statistics modules also contain very basic references to “theory building” as part of a falsification-focused approach.

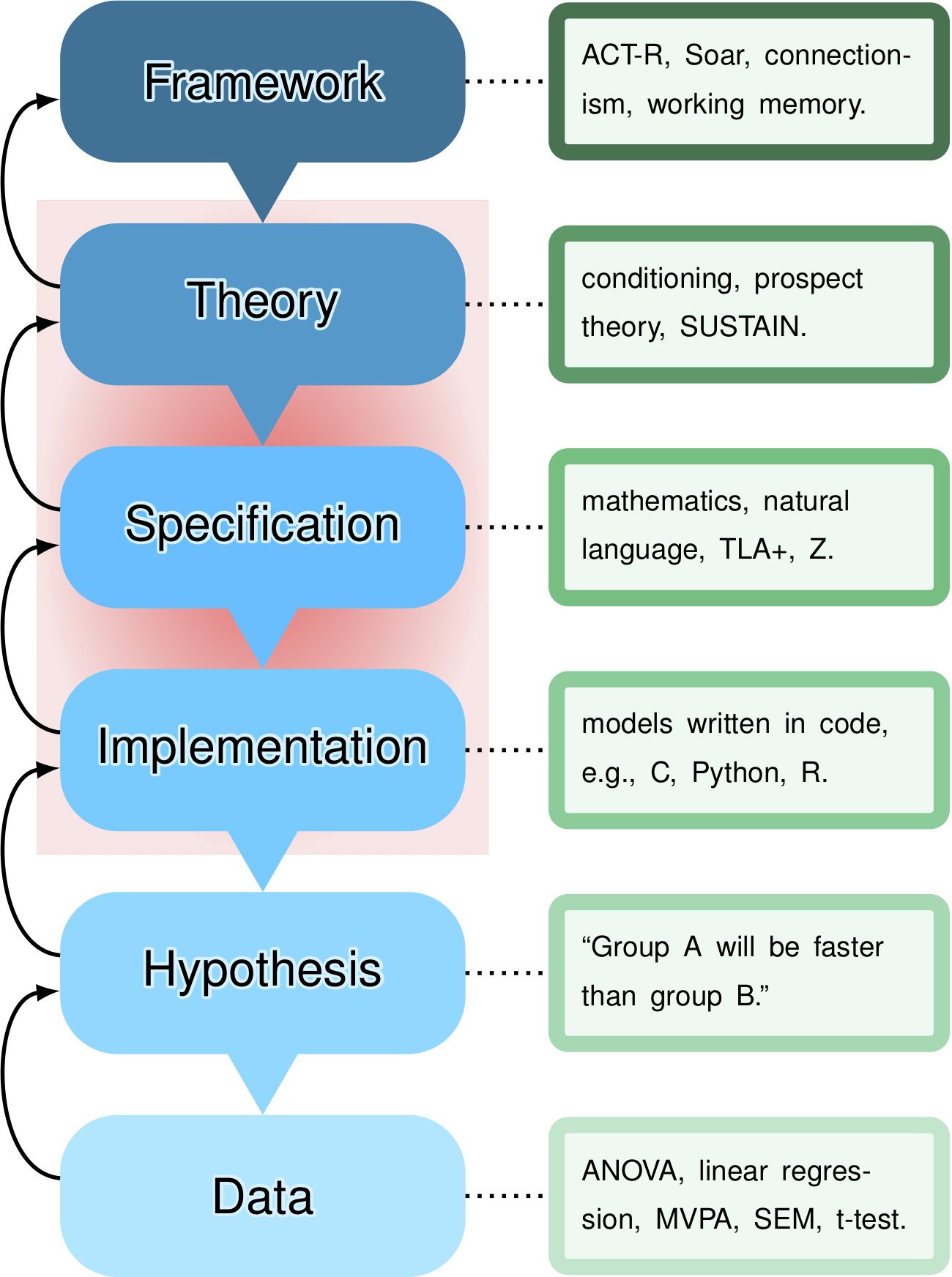

On the other hand, a specific module on “how to build theories” in undergraduate degrees is indeed typically lacking. It could be created but will be something incredibly difficult to get right and succeed pedagogically. We propose this might be for two related reasons: a) creating a novel theoretical account, or indeed building one from modifying existing theories, is extremely difficult for everybody. This is why in part we suspect that in the status quo certain people tend to avoid working in the red area of our path model’s depiction in figure 2, when that is where more focus is actually needed. The step in our path model called “theory” is the hardest one and — tangentially — certainly not something that only computational modellers should care about. Everyone, whether they realise it or admit it, if they are trying to figure something out, cares about theory. In addition, b) given how hard theory building/ the red area is in practice, imagine how much harder it will be to teach it. Pedagogy requires highly skilled individuals dedicating their lives to learning skills and how to teach others skills. How to build theories is what the whole of philosophy (and history) of science studies. So it is perhaps unsurprising given all this that psychology departments do not, or cannot, provide such a dedicated module. But that doesn’t mean it can be ignored or not taught.

This all being said, we do not take such a strong pessimistic outlook going forwards, hence why we wrote this manuscript. Realistic and helpful steps that can be taken to address theory building, in addition to reading our paper and thinking about how modelling can be applied to your work, is to actively engage with theoreticians in psychology, neuroscience, and cognitive science as broadly as possible. There are experts out there who make it their life goal to develop theories and, sometimes in lesser part, teach others how to do that also. We hope that any students/faculty reading this blog post might consider asking for/discussing a module that involves teaching and engaging with theoreticians’ and modellers’ works.

Probably related to the undergrad curriculum question but what do you have any advice on how someone who hasn’t been trained in comp modeling could “responsibly” start dabbling with it? Or should any serious work on the implementation step only be done in collaboration with a computational modeler?

We suggest people try working through toy examples like the one with the pizzas we work through in the paper (see section The pizza problem). And then try to make their own, in the simplest way possible. Then, perhaps by doing that for several explananda, your feeling about yourself in the process will change or settle. Start with a natural language sentence, then pizza model it! We go through the basic steps of very simple theory, to very simple specification, to very simple implementation, and you can too.

After all, this is the process, even more than the core methodological skills, that is required to make a simple model. The methods skills can come later and are a process of ongoing growth and change through one’s modelling life anyway. But the key is to grasp the endeavor, and start, rather than focus on the fancy bells and whistles or feel intimidated by them. The ability to begin with the statement in natural language and then even get to the first step of specification is thrilling!

For the second part: ideally, yes. But it’s not a requirement, and we think that is important to emphasize that. Collaborating with someone who already models will give you a chance to work with somebody who is more experienced and you will likely learn a lot. To sum up though, we want to emphasize that computational modelling is something everyone and anyone can effectively engage in, with little extensions from the skills and mindset they are asked to acquire in most undergrad psych degrees in 2020. For a list of modellers in cognitive science you might want to check out this list: compcog.science.

Pizza Problem Questions

Is “2 pizzas is more food” a theory in this context? And the pizzas are our data, right?

“2 pizzas is more food” is a hypothesis. It can be seen as a hypothesis based on our gut feeling (not an implementation). So we enter the path model at the hypothesis stage and then move to collect data, i.e., measure the amount of food in the pizzas.

So where would you fit the data that intuitively, people would prefer the two pizzas? Or is that entirely outside the metaphor you’re using?

The fact that people, we, intuitively think 2 pizzas is more food is the core of the pizza problem: an expectation violation (see section Model of psychological science). Rule two for constraining movement in our path model says that moving downwards is only possible if an expectation violation is resolved. So, in the pizza example, we can be seen as entering the path model at the hypothesis step. Our hypothesis is “two 12’’ pizzas are more food than one 18’’ pizza”, so we measure them (this is obviously not explicitly done because it’s a simple example, but imagine we order both options and measure the food in each). Now the data tells us our hypothesis is wrong. So we must move upwards to an appropriate level and figure out why we were wrong.

Path Model Questions

So does the downward stream correspond to a hypothetico-deductive approach and the upward stream to an inductive approach? Or is that too simplistic?

This is something we discussed when we were writing this up. Mainly for reasons of article length (there was a 5,000 word limit) we, Andrea and Olivia, decided not to go into this potential interpretation of the path model. To get everybody on the same page, inductive reasoning is when our premises are taken to provide some evidence for the truth of our conclusions. For example, all our lives we see ravens that are black so believe that “all ravens are black”. This of course could be false if we encounter a non-black raven (recall Europeans discovering black swans). Deductive reasoning, on the other hand, is when our premises are used to reach logically certain conclusions. For example, all ravens are birds, my pet is a raven, therefore my pet is a bird. Science uses all these kinds of logical inference to various extents including abduction.

One thing to bear in mind as a limitation of the typical hypothetico-deductive model of science is that it does not explicitly in its typical formulation include modelling or theory development in a way that satisfies us (e.g., it ignores underdetermination). It merely mentions steps that take us from hypothesis to data collection, so within the context of our model it doesn’t really emphasise theory or any of the other steps in the red area of our figure 2: theory, specification, implementation. The red area is where we want to draw the most emphasis in this paper (see section Model of psychological science). This is a part of psychological science that we propose is often left out with serious repercussions in terms of scientific integrity, openness, reproducibility, and so on.

Can (or can’t) we think of examples where a field was operating rather model free, then models entered and shifted the focus away from what turned out to be actually more important later on, e.g. due to the necessary simplifications?

In our understanding of how science is carried out, there are always models at play. The issue is that they need to be made explicit.

Then why do you say “plz make comp models” if there is no model-free science?

The emphasis should be on the “make” as in make your models explicit through the use of computational instantiation. Also it’s a meme — well-known to be caricatures of the real world. It also touches on the message that making a computational model will force you to acknowledge that your science is not and cannot be model-free, even if you want to think it is for whatever reason.

Should open theory as you propose it in the paper undergo the same preregistration process as other parts of the experimental process?

Being pedantic and emphasising the word “should”: no. We don’t believe that such a tool makes sense for open theory because as we will discuss below there are other mechanisms that allow for constraining our science. We also do not believe that scientific prescriptivism facilitates useful work. This is a good chance to clarify that our path model is merely a description of the process of doing science. So we can take an existing literature and plot its path. It is able to account for any scientific act. If there are scientific acts (including malpractice, HARKing, etc.) that our account does not have the ability to describe (including ones that we can describe as skipping steps), we need to amend our model (see section What our path function model offers). In other words, we wish for our account to be a description of science as is currently understood. And to facilitate talking about scientific acts in useful, transparent ways.

Going back to the question, however and discussing the role of preregistration, we believe our path model depicts (the bidirectional arrows) how strong constraints from one level to another can percolate up/downwards and refine the other levels. What we mean by this is that following the path model itself allows for the types of constraints (that data modellers use preregistration for) to be applied at every step. In other words, preregistration and related tools are a way to diminish various forms of inadvertent or purposeful scientific malpractice at the hypothesis and data levels, and in some cases to promote openness and replication. Preregistration was adopted in psychology and neuroscience from clinical trials and it serves its purpose well. It plays the role that supervening theories or formal models could play, i.e., to constrain the space of hypotheses and data collected. However, in the clinical trials literature they do not typically derive hypotheses to test based on theory, they merely compare groups of patients when administered different or no drugs. So preregistration is extremely useful in such cases since no top-down control exists from a supervening theoretical account — there is only a hypothesis (see section Model of psychological science). It is completely unbounded and researches even if extremely careful are likely to fall into questionable research practises.

Final Comments

We both really enjoyed this and it has really helped us understand how junior researchers see and understand our work. Thank you again to Anna Henschel and Stephanie Allan!

Related Reading

Cite

@misc{guest2020path,

author = "Olivia Guest and Andrea E. Martin",

title = "Path Model Q&A",

year = "2020",

howpublished = "Blog post",

url = "http://neuroplausible.com/path"

}